Implementing a Variational Quantum Algorithms module in QuTiP

About me

I’m an undergraduate student at the University of Sydney, studying Physics and Computer Science. I’ve worked on a few quantum computing projects in the past and was really excited to be awarded a microgrant by the Unitary Fund to work on this project. My personal website is available at benbraham.com.

Background

Many groundbreaking quantum algorithms (e.g. Shor’s, Grover’s) require quantum computers with a large number of qubits and high fault-tolerance to produce useful output for non-trivial problem instances. While this is likely some time away, there exist algorithms that aim to leverage the current power of noisy intermediate—scale quantum (NISQ) systems. Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) are a hybrid classical-quantum type of algorithm in which parameterized quantum circuits (PQCs) are optimized, with an objective function being evaluated on quantum hardware and the parameter update occurring on a classical machine.

One current area of interest in VQAs is that of the “initialization” for the algorithm. Problems are described by a quantum circuit, with its structure based on a circuit ansatz - usually inspired by the problem one wishes to solve. The performance of the algorithm is heavily influenced by the circuit structure, as well as the initial parameters of the circuit. It is therefore worthwhile to have the tools to test VQA formulations on a classical simulation of a quantum system, before expending time and resources to apply it on real quantum hardware.

QuTiP is a open-source python project for simulating quantum systems. In this project, I designed and wrote an implementation of a VQA module for QuTiP’s qutip-qip package, which allows users to define and evaluate the effectiveness of VQAs on their local machines.

Module Overview

Most quantum algorithms deal with quantum circuits, which are made up of quantum gates. In QuTiP’s qutip-qip package, there exist classes --- QubitCircuit and Gate --- which simulate the dynamics of quantum circuits.

For VQAs, we now want these gates to be parameterized. In addition to the gate parameters, we want initialization options, which are fixed throughout the optimization process, to be easily defined in one object. For these purposes, we define two new classes, VQABlock and VQA, which are abstractions on Gate and QubitCircuit, respectively.

1. The VQA_Block class

The VQABlock class encapsulates one component of our circuit and can store the action of one or more quantum gates. It can hold parameters, or keep note of how many free parameters it needs as input to be translated into a gate on the quantum circuit.

In quantum computing, all quantum gates can be described by unitary operators. Our VQABlock class has a method that will generate a unitary operator for the quantum circuit; but crucially, the value of this operator can change based on the parameters the VQABlock receives.

The VQABlock holds information about the operator it can generate, the parameters it needs, and methods to compute derivates of its operator. Using this information, the algorithm can compute gradients of its cost function. The optimization process is thus a loop in which VQABlocks are evaluated to inform the minimization of the cost of a circuit.

2. The VQA class

The VQA class holds information about the problem being optimized. It has methods to run optimization procedures with various options, such as the number of qubits required, the number of layers --- or repetitions --- of the circuit, and the optimization method to use. Here, we allow access to all of the function minimization methods available within the scipy library, as well as allowing user-defined optimization methods.

One part of the optimization process is specifying a “cost function” which the optimizer can use to assess the performance of a particular parameter set. In the case of a real quantum computer, the only output we have comes from taking measurements of the system. In quantum computing, these are usually represented as “bitstrings”, which encode the measurement outcome. For example, the measurement outcome of a two qubit system with one qubit measured in the |0> state, and another in the |1> state can be represented by the bitstring |01>.

If the cost method is set to BITSTRING, then the user needs to provide a function that takes in this string of 1’s and 0’s, and returns the associated cost.

Because we’re performing a quantum simulation, we don’t just have to deal with measurements --- we can “peek under the hood” of the simulation to get more information, including the actual state of the system before measurement. With this, we allow two more methods for specifying a cost:

-

If the cost method is set to

STATE, then the user can provide a function that takes in a quantum state and returns a cost. -

If the cost method is set to

OBSERVABLE, then the user can provide an observable and the cost becomes the expectation value of that observable in the final state of the circuit.

The VQA class stores a list of VQABlock instances, and can perform an optimization of their free parameters with a number of different options.

By allowing VQABlock instances to take more complicated structures and custom functions that generate their unitaries, we enable a range of quantum control problems to be approached within the framework of a PQC. One such abstraction is the Parameterized_Hamiltonian class, which can sit in a VQABlock within the circuit. On the side of the user, it’s easy to define different types of VQABlocks with different methods for generating unitaries, and let the module decide how to compute gradients for you.

Below I have included a general example of how the module can be used, in which a combinatorial optimization problem is approached using a VQA.

Example

Here we will look at how one might implement a VQA in this module. To begin, we’ll introduce the partition problem.

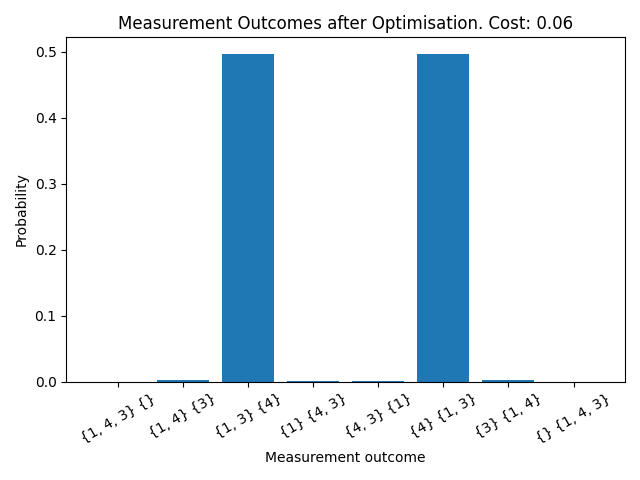

The partition problem asks if there is a way to partition a set of integers, $S = [s_0, s_1, \dots s_n]$, into two subsets $S1$ and $S2$ such that the sum of elements in each of these sets is equal. For example, the set $S = [1, 4, 3]$ can be partitioned into the sets $S1 = [1, 3]$, $S2 = [4]$. The optimization version of this algorithm asks for the partitioning that minimizes the difference in these two sums.

This problem is known to be NP-Hard, so there is no known efficient classical algorithm for solving it. One way of finding approximate solutions to this (although it is not yet clear if VQAs give a speed-up here), and other combinatorial problems is through a VQA known as the Quantum Approximation Optimization Algorithm (QAOA).

The QAOA gives us a circuit ansatz that we can use to approximate solutions to combinatorial problems. In general, if we can encode the solution to our problem in the ground state of a Hamiltonian, $H_P$, and we can pick another Hamiltonian, $H_B$, that doesn’t commute with $H_P$, then our circuit takes the form:

$$ U(\beta, \gamma) = \prod^p _{j=0} \quad e^{-i\beta_j H_B} e^{-i \gamma_j H_P} $$

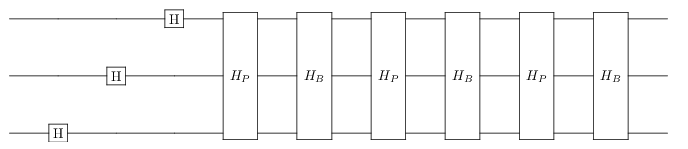

where each $\gamma_j$ and $\beta_j$ is a free parameter, and we repeatedly apply unitaries generated by $H_P$ and $H_B$, $p$ times.

We now need to work out how to encode our problem in terms of the ground state of a Hamiltonian. The cost of our solution is given by the difference of the sums of the two sets, i.e. sum(S1) $-$ sum(S2). As $S1 \cup S2 = S$ and $S1 \cap S2 = \emptyset$, this is equivalent to taking a weighted sum over $S$, where we assign a weight of $-1$ to elements partitioned into $S2$. We can describe this with the Hamiltonian

$$ H_P = \left(\sum_{s_i \in S} \quad s_i \sigma_z^(i) \right)^2 $$

where $\sigma_z$ is the Pauli $z$ operator, and the superscript indicates it acts on the $i$th qubit. Clearly the lowest energy state for this Hamiltonian corresponds to the partitioning of the elements of $S$ that minimizes the difference between sum($S1$) and sum($S2$). Now that we have encoded the cost minimization into the energy levels of a Hamiltonian, we’re ready to translate our idea into code.

After defining our Hamiltonians as quantum objects (matrices with more bells and whistles) with QuTiP’s Qobj class, we can define our VQA as follows:

This code has constructed a quantum circuit that looks as follows:

After calling the optimize_parameters method, we can plot the results of the optimization process in terms of the measurement outcome probabilities.

Here, we have passed in the label_sets parameter to the plot function, which labels measurement outcomes by their corresponding set partitioning of the problem instance.

There are many parameters to tweak here, such as the number of layers used, initialization conditions, the optimization algorithm parameters and constraints, as well as gradient computations. It is my hope that this tool allows anyone to dive straight into VQAs.

References

Other examples, including the max-cut problem examined in the original QAOA paper, can currently be found on my GitHub.

I opened an issue to discuss with the QuTiP admins how to best include these features into the main qutip-qip project codebase.

Future work

There are always possible optimizations and additions for a tool with this kind of scope. There have already been some great suggestions on the associated GitHub Issue for integrating this with other QuTiP tools, and when the pull request goes up, there will likely be more. Please feel free to contribute or join the discussion!

This project has laid the foundations for a very general set of tools to define VQA problems. The code written should be robust enough that expansions to allow more specific formulations are possible.

Acknowledgements

Throughout my work on this project, I’ve been privileged to have the supervision of A/Prof. Daniel Burgarth and Dr. Mattias Johnsson at Macquarie University.

Thanks to the Unitary Fund for supporting my project, and for all the advice and chats along the way!